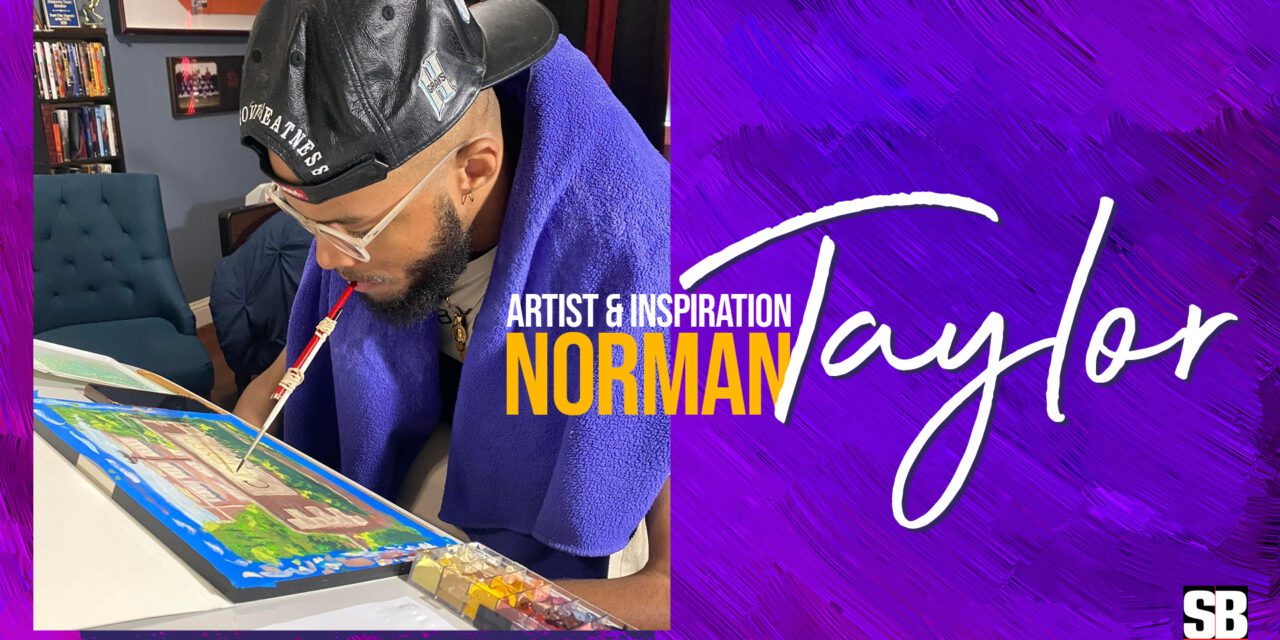

BY SCOTT ANDERSON

Norman Taylor has learned one important life lesson that has taught him to “go with the flow.”

“Life’s not going to stop,” he said. “You’re not going to get a certain time back, so try to do as much as you can with your time.”

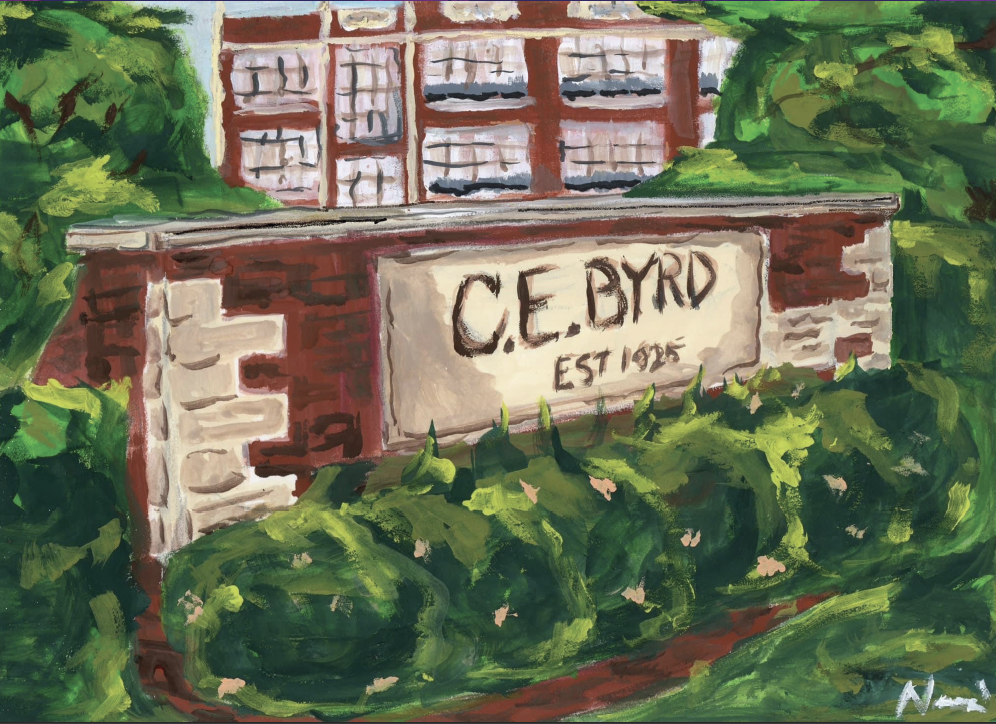

Taylor does a lot with his time. In August 2020, the 29-year-old artist sold his first painting. Elizabeth Eldridge, the mother of one of Taylor’s former teammates at C.E. Byrd High School, had seen a video of Taylor sketching.

“She was like, ‘If you ever wanted to get back to doing it for real, let me know. I would really like one,’” he said. “I’ve been rolling ever since.”

The Eldridge family not only bought a painting from Taylor. They helped him set up his business, too. He takes commissions for original paintings and sells prints of his work at notbyhand.us.

Art has been a longtime interest for Taylor. In second grade he entered the Talented Arts Program. But he didn’t fancy himself a painter.

“I never liked painting,” he said. “I just liked to sketch.”

He got serious about his art at Broadmoor Middle School. But he wasn’t thinking about becoming a professional artist. He had other dreams he was chasing on the football field.

“At 9 years old, I knew I was going to go to high school, get recruited and play at USC for Pete Carroll and then get drafted by the Chicago Bears,” Taylor said. “I knew what cars I was going to have — all of that.”

Life does not stop, but sometimes it changes directions without warning.

Taylor remembers Sept. 16, 2008, like it was yesterday. It was just two days after his 15th birthday. He was on the practice field, preparing for Byrd’s Week 3 matchup against West Monroe, when the unimaginable happened.

“We call it a sweep drill,” Taylor said. “It’s a form-tackling drill. “When I went down to tackle my teammate, whiplash — a freak accident.”

The doctor diagnosed it as a C7 incomplete spinal cord injury, meaning his spinal cord was still intact. It was better than a C7 complete, Taylor said.

“That means the spinal cord is completely severed,” he said of a C7 complete. “For them, it’s always that 0.000001… whatever percent chance. For me, the percentage for regaining movement was higher.”

Suddenly, the young man who had played multiple sports from the age of 5 without even a broken bone was unsure of his situation.

“I was so naive to the injury that when they said, ‘You’ll be back,’ I thought I would be back playing by the playoffs,” Taylor said. “I was 15. There was not as much information about stuff like that back then. I was oblivious to how severe the situation was.”

Taylor had surgery to repair his damaged spine and then made arrangements for rehabilitation at Our Children’s House at Baylor in Dallas.

“I left for Baylor Oct. 1, 2008,” he said. “I spent 2 months and 22 days there. I came back Dec. 22.”

Taylor was wheelchair bound when he returned to Shreveport. He began homeschooling that December to keep up with his classmates. That’s when the gravity of the situation began to settle on him.

“You drop into a certain depression,” he said. “From the time I got home, I didn’t really leave my room unless it was for a doctor’s appointment or to eat, or to be homeschooled. I didn’t feel like I needed to be social. I was afraid to go back because I was in a different physical state than I was at first.”

In April 2009, he returned to the Byrd campus. The plan was to be on campus for a few classes, up to half a day.

“I ended up the next day just going back full time,” Taylor said. “I realized when I got back, they were just so happy to see me it didn’t really matter.”

Taylor said he spent his junior year readjusting to being among a lot of people again. But that wasn’t his biggest challenge.

“I was having to deal with going to PT rather than going to practice,” he said. “It was a different type of working out, regaining my mobility.”

In his senior year, Taylor was discharged from rehab because his progress had plateaued, he said. “Like everybody else, you have fun your senior year,” he added.

He started college at LSUS the next fall. That was a wake-up call for him.

“Out of the nine classes I took, I probably passed three,” he said. “I wasn’t taking it seriously. You can tell somebody something all day. But when you’re immersed in it, you realize by the time it’s over, ‘Yeah, this is real.’”

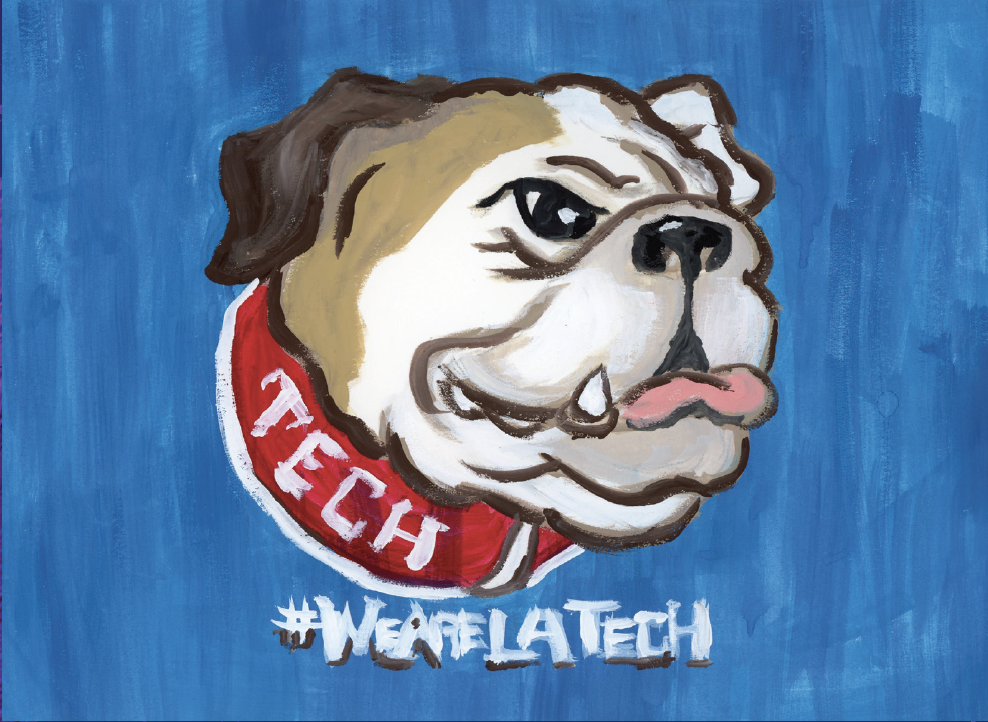

He finished that semester with a 1.11 GPA. “I think they were generous with the .11,” he said. So, he transferred to Southern University, where he found a good fit.

“It’s more like a small family, as far as people reaching out to you, saying you should probably do this,” he said. “Even if you don’t know what you’re going to do.”

Taylor received an associate’s degree from Southern, then returned to LSUS, where he received his bachelor’s degree in humanities in 2018.

Taylor set art aside after high school. When he picked it up again after college, it started out as just a pastime. But it ignited a spark in him. He continues to study art the way he once studied football.

“I realized I was still pretty good at this,” he said. “It went from there to watching YouTube videos. I said, ‘I can probably get better.’ Asking other artists how they did things. From there, it starts becoming a thing you’re obsessive with. It’s kind of like football. You get to where you actually like it. You’re not just out there playing.”

Taylor’s competitive nature kicked in, too. Instead of competing against other artists as he had competed on the football field, he began competing with himself to become a better artist. So, as he did in football, Taylor immersed himself in practice.

“Anybody can draw,” he said. “A lot of people think it’s something you’re born with. It’s really something you develop. They call it neuroplasticity. Those transmitters in the brain. You wonder why Floyd Mayweather is such a good boxer. It’s because he does the same thing over and over.”

In addition to being competitive, Taylor also is a perfectionist. So much so that in the early days of his art career, Taylor wouldn’t accept down payments for his work.

“I treasure quality over quantity,” Taylor said. “If it’s not up to what I like, I will have them throw it away and start over.”

Thomas Williams has been assisting Taylor since 2013 and has seen that perfectionism in action.

“People don’t know how many masterpieces he’s done that only the trash can has seen,” Williams said.

Williams admits to rescuing one of those works Taylor discarded. It hangs in the Williams house today. It’s a symbol of the respect Williams has for Taylor, his artwork, and his process.

“Me being with him all the time, assisting him and watching him, people don’t understand the process he goes through,” Williams said. “Seeing him go from a blank canvas to a finished painting, it’s amazing. I’m blessed every day to see him go through the process.”

Taylor has a job at General Dynamics. He continues to paint and anticipates having his first art show in February. He also is designing T-shirts and hoodies that feature his artwork.

“I honestly don’t know what’s next,” he said. “If I knew I would tell you. The wind would have to blow very hard for me to know.”

Reflecting on his life, Taylor has a bit of advice for young people, especially young athletes.

“Don’t play to not get hurt,” he said. “That’s dangerous. You’re putting yourself in more danger. Don’t cheat yourself or your teammates. Or the sport. The injury isn’t the hardest thing to live with. I would think that regret is.”

He also wants to remind anyone to always remain a student of the game, regardless of what their game might be.

“You want to make everything easier on yourself,” he said. “That’s what a lot of people don’t want to do. With any profession, you have to learn about it. You have to learn what makes it easier for you. If you’re working yourself to death and there are easier ways out there, you’re just being stubborn.”

Taylor is glad that art has written a new chapter for his life.

“For the longest time, I was the young man at Byrd who got injured playing football,” he said. “Now I am Norman Taylor the artist. That’s what I am most proud of, switching my identity to, ‘This is who he is now.’ That’s just a part of the story.”