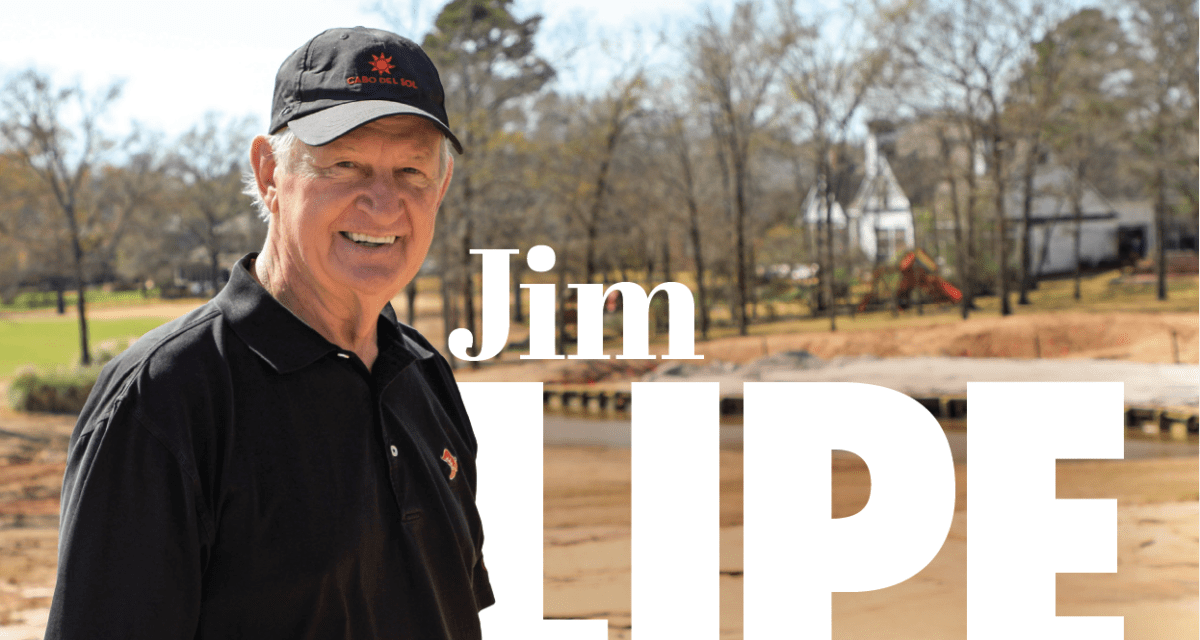

Jim Lipe

Impacting the World of Golf

by – Byron May

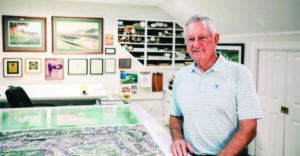

If you threw out the name Jim Lipe at most family gatherings, you may get a blank stare. But if you mentioned his name at hundreds of top-rated golf courses around the world you would get either admiration for the amazing courses that members enjoy, or occasional anger for how challenging these courses can be. You see, Jim Lipe is a landscape architect and golf course designer and is considered one of the best in that industry. He has designed and managed the construction of elite golf properties throughout the U.S. and in several countries.

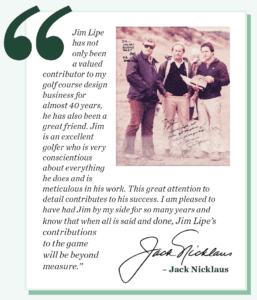

I’ve known Jim for close to 30 years. We were in the same weekend golf group at Southern Trace for over a decade. He’s been a really good player all his adult life. I knew Jim was involved in Golf Course design, but it wasn’t until the Spring of 1990 that I learned firsthand what a force he was in that industry. Jim invited our group to North and South Carolina to play the elite courses he and Nicklaus Design had either designed and built or renovated. Jim had become a big deal in the Nicklaus Design and Renovation business and a close friend and right-hand man of Jack Nicklaus. That week we played 6 of the most prestigious golf courses in the country including historic Pinehurst Number 2. We even stayed at the owner of Pinehurst National Golf Club’s house in North Carolina overlooking the 18th green as well as one of Jack’s homes on Pawleys Plantation Golf Club in South Carolina. For a golf nut like me, it was a trip that was as good as it gets. On that trip I learned firsthand how admired Jim is in that industry. At every course we played we were treated like royalty because we were Jim’s guest. Pictures of Jack, Jim and course owners adorned the walls. Locally, Jim worked on the David Toms 265 Golf Academy and is currently in the process of revitalizing the Southern Trace Country Club course.

I recently asked Jim to sit down with me and talk about his career.

When did you decide to pursue golf course architecture as a profession? I graduated with a business degree at LSU, and I was drafted and got on the bus to head to Fort Polk. And for some reason, only the Lord knows, he diverted us to New Orleans. I flunked the physical. They told me to go home, have my knee operated on and report back in 10 months. A lot of things happened during that time. I had to make a decision if I was gonna go back to school. My dad always wanted me to be a lawyer. I always leaned toward golf course design. I didn’t really know if there was a profession there for me because at that point in time, we’re talking about 1969, there weren’t very many golf course architects. I took the test to get to law school. I could have gone there. I took the entrance exam to the Graduate School, and I did well there. I went over to the landscape architecture department at LSU, not knowing a thing about it. I walked in there and, low and behold, I found out that LSU was the number one landscape design school in the nation. And still is to this day. They accepted me. This was in the summer, and it just so happened—again, the Lord’s direction I believe—that fall they were going to take students in from other disciplines to enter into a three-year Master’s program. It just seemed perfect for me with my whole situation. My wife was working in Baton Rouge, and we were loving our life in Baton Rouge and so I entered that program, one of nine people. I was the only one to graduate on time.

What was the first job you had in the business? A golf course architect named Bill Newcomb hired me during a summer internship, and then he hired me to go to work with him in 1972 as a design associate, with a two man firm, in Michigan. And we stayed together for about three years and then we became Newcomb Associates. I entered into a partnership with him and that lasted another five years. And then I went out on my own because, quite frankly, in Michigan, in the Midwest, there just wasn’t very much work. I had some opportunities that were given to me and so I was able to do that on my own. And then in the early 1980s, they were shutting the lights out in Michigan, if you remember those days. It was a good time to bring my wife back to Louisiana, which I always told her I would do. Shreveport was the closest town with an airport close to where she grew up in Natchitoches, and so we settled here in Shreveport.

became Newcomb Associates. I entered into a partnership with him and that lasted another five years. And then I went out on my own because, quite frankly, in Michigan, in the Midwest, there just wasn’t very much work. I had some opportunities that were given to me and so I was able to do that on my own. And then in the early 1980s, they were shutting the lights out in Michigan, if you remember those days. It was a good time to bring my wife back to Louisiana, which I always told her I would do. Shreveport was the closest town with an airport close to where she grew up in Natchitoches, and so we settled here in Shreveport.

I know for many years you’ve been a big part of Jack Nicklaus’ design group. When and how did that come to be? Not long after I’d been living here, I was contacted by the Nicklaus Company to see if I would be willing to go and live in Cornwall, England, and build a golf course. Really all I had was a plan, but I had the top shaper in the country, Bob Steel, and we lived together for 18 months and built a golf course—Jack’s first international course anywhere. He only went over there once a year for the British Open and he stopped in. He made two trips in 18 months, so I pretty much built it on the seat of my pants. The idea was if or when Bob Cup, a senior designer associate, leaves then I was going to take his position in the company and that’s what happened. Jack was very happy with the golf course. It held eight Benson and Hedges tournaments in the European Tour. And I came back, and Jack says, “OK, you ready to move to Florida? Everybody that works in my company lives in Palm Beach.” And I said, “Jack, my father-in-law, just built a home for us. I can’t walk away from that home right now.” And he said, “OK, let’s give it a go for a year and see what happens.” And Juliana and I are still in the same house 39 years later. Jack’s been very, very kind and good to me.

Would you expand on your long relationship with Jack Nicklaus? We’ve had, you know, obviously a good relationship. What he’s always said he appreciated about me was that that when he looked at something and I looked at something, we saw the same thing. That was a benefit for him because I’ve seen him with other designers, and it just didn’t come off that way. So, he always felt comfortable just turning things over to me. And so that was kind of our trust. It was good right from the very beginning, and we became good friends. We’ve worked in New York, Sebonack, and Ferry Point. We’ve done a lot of things together with our wives. I think we’ve been to several Broadway shows together. Jack and Barbara asked my wife, Julianne, and I, to be their guest at the President’s Cup in South Africa. And we flew over there on the plane—we were their guests. That was unbelievable. But we’ve just become good friends. And so, we talk every couple of weeks these days and have a good friendship. We’re not doing as much work together because most of the work these days is renovation work. There’s not a lot of new stuff, at least in this country. There is in Europe and the Middle East and in in Asia, but not so much in this country yet. So, I chose to stay here in this country and work rather than doing all that travel—except to Mexico. I still go to Mexico and do all the work down there.

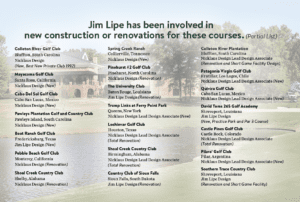

Over the years, how many golf course design projects or renovations have you been part of? You know, I’ve never counted them. It’s kind of strange because a lot of times I will start a project and then along the way, someone else will take it over or they will start a project and I will finish it. I have to believe it’s somewhere in the 250 range.

Could you describe the different phases a new golf course has from conception to completion? Well, you start off the process by working with the ownership to get the best piece of land. Sometimes that will be several trips, to several different pieces of land, like when I worked with Hal Sutton at Boot Ranch. We looked at three pieces of land before he settled on purchasing the present Boot Ranch parcel.

Then I will embark upon doing several routings and working with the master plan ideas, trying to help the ownership develop a master plan.

Once we settle on a routing plan, then we go into what we call construction drawings. The first and most important is the grading plan—that’s going to determine a lot of different things: your grassing plan, your irrigation plan, cut and fill plans, how much dirt you’re gonna be moving.

And then we go from there. Whether it’s me, or if I’m working with Jack, he’ll make various trips like walking and staking early on and he’ll move things around and stake it and we’ll walk it and he’ll move things or change things, and then he’ll give me designs and he’ll do little sketches.

From there we get into construction drawings and then we get into the actual green designs. Jack or I will draw up the green designs. We put together a construction package, put it out to bid, call contractors to the site. And we do what’s called a construction pre-bid walkthrough so that every contractor knows exactly what we’re trying to accomplish, so we can get the closest bids we can.

Then we settle on a contractor and we go to work. And then I make site visits throughout the project as they do different phases of work. They might work on six holes. I make sure they understand what to do. They do that, I come back and go to another six holes or four holes or whatever it is. But I come when the contractor needs me for approvals. And then we look at other stuff. So it’s a continuous process of anywhere from a year to 18 months for a project.

So it’s a lot like a house? It’s exactly like a house. It’s built in layers and stages, as you go through it. People ask me about renovations versus new designs. Renovations are much harder—for me—because of my critical eye. I see certain things that I’ve learned from Jack and I know what’s important to him. So, it’s important to me too. And that is making something look like it was the original terrain and that’s hard to do when you’re working with existing complex moundings, surrounds, drainage, all that sort of stuff. It’s very tedious and that’s why it’s so important for us to have such a good shaper. We have Cliff Hamilton on the project and when I tell him what I’m looking for, he understands it. It’s not like I have to stand there and beat it into his head. Of course, then you have the irrigation situation, which we had already put in new irrigation and now we had to pull out some of it. We tried to minimize that for cost reasons. But again, it’s all about the tie-in, so you don’t have hinges, you don’t have creases. It looks like it’s the original design. That’s the hard part of renovation. We did an excellent job at Southern Trace.

How do you think the renovation of Southern Trace golf course you’ve just completed stacks up against the elite courses in our state?  Well, I think it’s definitely going to make a move way up the list. It had fallen kind of in disrepair, and it originally was very highly regarded. So from that aspect–from playability, difficulty, challenge, fun—it was always highly regarded.But since 1985 I don’t know how many golf courses have been built in this state, but some pretty darn good golf courses have been built in the state. So, will it make it all the way back up to the top where it once was? I probably doubt that. I know a lot of it is generated through different promotions and so forth. But I think it definitely will be highly regarded. We’re getting to have some state tournaments coming in. I think when the people in the state see the work we’ve done, they’re going to speak very highly of this club. Whether it’s to 1,2,3,4, I don’t know, but I think it’ll be way up there.

Well, I think it’s definitely going to make a move way up the list. It had fallen kind of in disrepair, and it originally was very highly regarded. So from that aspect–from playability, difficulty, challenge, fun—it was always highly regarded.But since 1985 I don’t know how many golf courses have been built in this state, but some pretty darn good golf courses have been built in the state. So, will it make it all the way back up to the top where it once was? I probably doubt that. I know a lot of it is generated through different promotions and so forth. But I think it definitely will be highly regarded. We’re getting to have some state tournaments coming in. I think when the people in the state see the work we’ve done, they’re going to speak very highly of this club. Whether it’s to 1,2,3,4, I don’t know, but I think it’ll be way up there.

What is the biggest challenge on taking a piece of land and turning it into a golf course masterpiece? Well, obviously, the great golf courses of the world are built on great pieces of land. You can’t turn a pasture into a great golf course. You can move a lot of dirt, but it would take 50 years for trees and everything to mature to a state where you would not know it was an original pasture. So, the hardest thing to do is find a great piece of land. Once you find a great piece of land, then it’s a matter of tying into that existing land, so, like I mentioned before, it doesn’t look like it you did anything. It looks like most of it was just there and that’s what people really enjoy. And when you can do that and come up with a very playable golf course that’s not very penal, it’s got some interest in the strategy and it makes you think. When you stand on tees—every tee out there— you should have some golfers thinking. It’s a thinking man’s game I think. If you just step up there and just don’t think about what you’re doing, just hit it, it’s kind of like the driving range. So, I think the hardest part is not messing up a great piece of land and doing your best on a difficult piece of land, but trying to make it so it’s fun, it’s a challenge, it brings people back, they have controversy, they talk about it. All those kind of things is what makes golf interesting in my mind.

tying into that existing land, so, like I mentioned before, it doesn’t look like it you did anything. It looks like most of it was just there and that’s what people really enjoy. And when you can do that and come up with a very playable golf course that’s not very penal, it’s got some interest in the strategy and it makes you think. When you stand on tees—every tee out there— you should have some golfers thinking. It’s a thinking man’s game I think. If you just step up there and just don’t think about what you’re doing, just hit it, it’s kind of like the driving range. So, I think the hardest part is not messing up a great piece of land and doing your best on a difficult piece of land, but trying to make it so it’s fun, it’s a challenge, it brings people back, they have controversy, they talk about it. All those kind of things is what makes golf interesting in my mind.

What golf course design project do you consider your best, and why? Well. People always ask me, ‘what’s my favorite course I’ve done?’ I could name six or eight. I enjoyed the Boot Ranch project. I enjoyed working with Hal Sutton. It was a wonderful piece of land. And I really was into the whole philosophy of what he was trying to create. May River was wonderful. Cabo del Sol down in Mexico was a wonderful piece of property. Great Waters was a wonderful piece of land. Mayacama out in California, a fabulous piece of land. There’s Spring Creek Ranch in Memphis. I always enjoyed that project and I think it’s one of our best golf courses. So, there are several that when I’m there, you know, I’m just loving it.

What project was the most challenging for you and why? Oh gosh, of all the ones I’ve done, the most challenging was in Taipei, Taiwan. It was built on the side of a mountain. It had nothing but cemeteries, all these temples and stuff built on the side of it. I had to route the golf course around all these temples, and we only had half a slope. So, we were always building a side slope and stacking them and that was almost impossible.

What was the most expensive gold course design and build that you were involved in? I never really got a handle on what the Taiwanese spent on that, but I’m sure it was a good chunk of money. It wasn’t the most expensive. The most expensive by far was Trump Golf Links at Ferry Point in New York because it was run by the New York Parks and Recreation Department and if it could be done  expensively… It was a landfill that actually shut down in 1965. That golf course supposedly cost like $226 million. Now, the regular golf course itself, just built on that landfill would have cost about $15 million. So, the other $200 and odd was all the engineering and stuff to build on top of the landfill, catching every drop of water that hits it, not let it run off, it was just bizarre. It was an interesting project, and it’s a really, really, really good golf course. If you’re ever up in New York City, you should go play it. The only reason Trump’s name is involved is that the last six weeks before completing the project, Trump negotiated a maintenance contract to build a pro shop and a clubhouse and a maintenance building he would operate. He’s done a wonderful job. Now they’ve actually kicked him out since January 6th but he was doing a terrific job. Matter of fact, we were going to have a U.S. Open there in 2024. I sent you the pictures that were Trump and Jack and Mike Davis, head of the USGA. We had a big meeting in Trump’s office. I can show you the plans where we were scheduled to alter two holes, but it didn’t happen because he and his wife came down the golden escalator not long after that meeting. Maybe six months.

expensively… It was a landfill that actually shut down in 1965. That golf course supposedly cost like $226 million. Now, the regular golf course itself, just built on that landfill would have cost about $15 million. So, the other $200 and odd was all the engineering and stuff to build on top of the landfill, catching every drop of water that hits it, not let it run off, it was just bizarre. It was an interesting project, and it’s a really, really, really good golf course. If you’re ever up in New York City, you should go play it. The only reason Trump’s name is involved is that the last six weeks before completing the project, Trump negotiated a maintenance contract to build a pro shop and a clubhouse and a maintenance building he would operate. He’s done a wonderful job. Now they’ve actually kicked him out since January 6th but he was doing a terrific job. Matter of fact, we were going to have a U.S. Open there in 2024. I sent you the pictures that were Trump and Jack and Mike Davis, head of the USGA. We had a big meeting in Trump’s office. I can show you the plans where we were scheduled to alter two holes, but it didn’t happen because he and his wife came down the golden escalator not long after that meeting. Maybe six months.

If you could design and build your own golf course, where would it be? Cabo. Because the weather is perfect 360 days a year. It’s got little mountains that works their way down to the ocean, the desert, the cactus, the palms. If you ever go to Cabo, you’ll never go anywhere else.

With all your traveling around the globe, what made you and Juliana decide on Shreveport as your home base? Her family is from Natchitoches. I told her I’d bring her back to Louisiana because we’re big LSU fans and we have friends here, Connie and Jay Pierson. Connie lived across the street from Juliana when they were growing up and Connie introduced me to my wife, Juliana. Shreveport

was close to Natchitoches.

Of all the people that you’ve played with during your life, who would you consider the luckiestto be? This guy named Byron May. He’s never seen a tree that wouldn’t knock his ball back in the fairway.