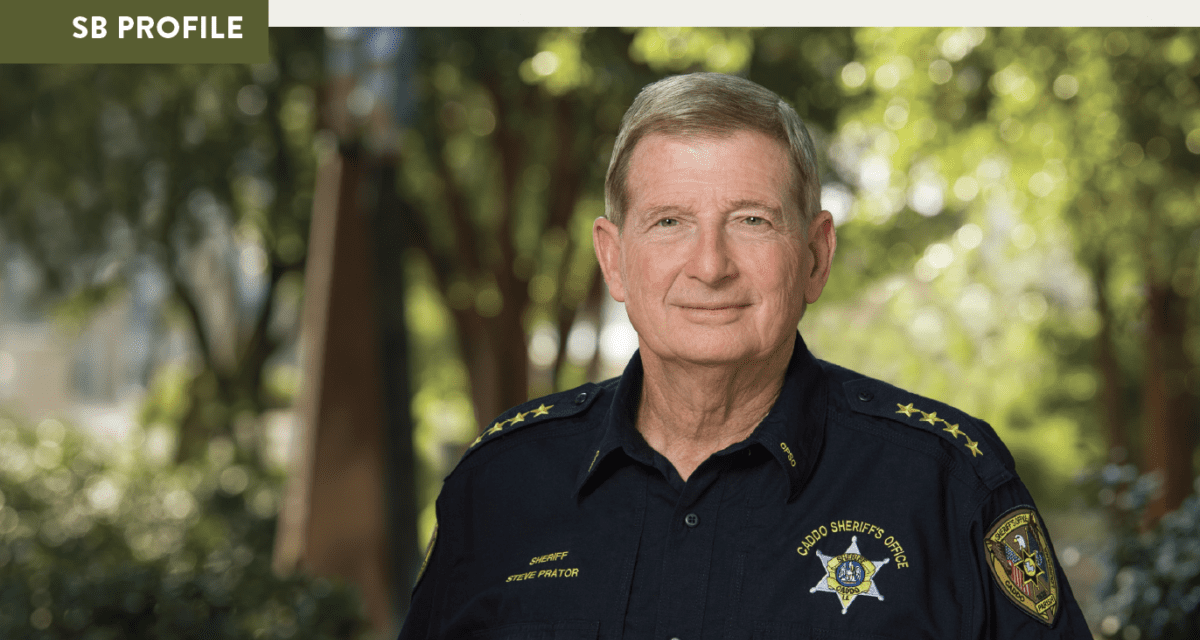

SB PROFILE

Caddo Parish Sheriff Steve Prator

BY SCOTT “SCOOTER” ANDERSON

In Caddo Parish Sheriff Steve Prator’s office, a huge organizational chart of the department hangs on the wall. The desk is neat and tidy — nothing extra, and nothing out of place. Guests are welcome to sit across from Prator in a comfy wingback chair. Next to the chair is a side table with a lamp and a family Bible. The only thing that feels extraneous in the whole room is the plush cow next to the Bible. It’s the only hint in the room of his upbringing and his life outside of law enforcement. “Growing up, we worked, and worked hard,” Prator said. “I raised cows. I love farming, being outside. I can fix anything.” “I was very fortunate to have the dad and mom that I had. They raised me right to treat everybody the same. Dad always said, ‘A Prator’s no better than anybody else, but nobody’s better than a Prator.’ That’s the way you treat people, like we are all the same.” Prator was born in Clarksville, Tenn. The family moved to the North Highlands neighborhood in Shreveport when he was in the second grade. He went to North Highlands Elementary School and Hamilton Terrace. He attended Byrd High School his freshman year, then transferred and graduated from Northwood.

He also was active in the Boy Scouts, achieving the rank of Eagle Scout. “I am proud of that,” he said. “That had a lot to do with where I stand today.” Prator admits that he wasn’t really ready when he took his next step after graduation and enrolled at LSU in Baton Rouge. “I was way too immature to be going to school,” Prator said. “I had gone down there on a scholarship. I had broken my foot in football. I went down on what was called a vocational rehabilitation scholarship. I primarily played and partied. School was not at the top of my list of things to do to have fun.” It was then that he fell into a career in law enforcement, almost literally. “I ended up falling off of the fraternity house,” he said. “I hurt my back. My father told me I was going to come home and grow up before I did any more college work.” So he returned to Shreveport. On Jan. 29, 1973, he started as an officer with the Shreveport Police Department. Without knowing it at the time, Prator had found exactly what he was looking for. “I didn’t grow up wanting to be a policeman,” he said. “But it had everything I needed. It was exciting, you got to help people, and it was outside. I didn’t have to sit at a desk, and that was perfect for me. I just fell in love with the job.”

He also was active in the Boy Scouts, achieving the rank of Eagle Scout. “I am proud of that,” he said. “That had a lot to do with where I stand today.” Prator admits that he wasn’t really ready when he took his next step after graduation and enrolled at LSU in Baton Rouge. “I was way too immature to be going to school,” Prator said. “I had gone down there on a scholarship. I had broken my foot in football. I went down on what was called a vocational rehabilitation scholarship. I primarily played and partied. School was not at the top of my list of things to do to have fun.” It was then that he fell into a career in law enforcement, almost literally. “I ended up falling off of the fraternity house,” he said. “I hurt my back. My father told me I was going to come home and grow up before I did any more college work.” So he returned to Shreveport. On Jan. 29, 1973, he started as an officer with the Shreveport Police Department. Without knowing it at the time, Prator had found exactly what he was looking for. “I didn’t grow up wanting to be a policeman,” he said. “But it had everything I needed. It was exciting, you got to help people, and it was outside. I didn’t have to sit at a desk, and that was perfect for me. I just fell in love with the job.”

In the next 19 years, Prator went on to work in a variety of departments — including robbery, homicide, and narcotics. He also formed the department’s first sex crimes unit. “I convinced my supervisor that you needed more specialization than just a detective working sex crimes,” Prator said. “I was fortunate enough to be involved in catching the Highlandrapist.” In those 19 years he rose through the ranks to sergeant. Then he decided to take on another challenge. “When the chief’s job came open, I applied with 42 other people,” he said. “Somehow I got chosen as a sergeant to be chief.” That’s when he got another real-life education from his father. “I’ll never forget going to my father and asking him. ‘Dad, how do you fire somebody?’ I have ended up firing hundreds of people over the course of my 30 years of leadership. When I was with the Shreveport Police Department, my nickname was ‘Terminator Prator’ because I fired so many police officers, mostly because of lax hiring practices years earlier.”

Prator served as chief of police for eight and a half years. It was time for him to pivot again. “At 27 years, I was able to retire from the police department, and I knew I wasn’t through with my career,” he said. “I retired and ran for sheriff. I got sworn in as sheriff in the year 2000.”

With that new challenge came another new lesson, this time in the politics of public service.

“Other than running for office, the job of sheriff is less political than the job of police chief,” he said. “As police chief, you answer to every politician; you answer to the mayor; you answer to the CAO; you answer to each of the city council members each time you go to a city council meeting. You answer to every pastor and every community leader. Everybody always feels like they are ‘over you.’

“When you get to be sheriff, and I didn’t realize this, all of a sudden it’s, ‘Can we have a minute of your time?’ I would much rather work for 250,000 people than I would for one person.” In Louisiana, the sheriff also serves as the tax collector — which put him in an interesting position at church one Sunday. “The pastor’s whole sermon was about how Jesus even hung around with the tax collector,” Prator said. “After the service, I told him, ‘That’s kind of a cheap shot. I’ve got to be the tax collector.’ Jesus hung around the sinners and the tax collectors. Well, I guess I fit both categories.”

Faith has always been a cornerstone in Prator’s life. But he struggled early in his law enforcement career with reconciling thesetwo areas of his life. “I had more trouble with it as a young officer,” he said. “I couldn’t understand how such bad things could happen to such good people. I had problems with the concept of me being the one to hold people accountable. As my faith matured, and as I matured as an officer, I realized that I was called into this profession. I was called into it to help keep people safe, and to separate those who will do evil from those who do good.”

Beyond his faith and his family values, Prator holds one passion that drives his work in law enforcement. “My passion is keeping people safe,” he said. “The criminal justice system is not broken, but it is certainly cracked.” It’s a singular focus he also appreciates in his favorite Hollywood lawman.

“Clint Eastwood. I like all of his movies,” Prator said. “Andy Griffith? It’d be great if life was like that. but it’s not. He’s the great community-oriented police person. Matt Dillon? He’s a great role model. He was a step above Andy Griffith. I always liked Clint Eastwood because he could always get the job done.”

Prator is especially focused on violent crime, like the rolling gun battle between two cars through the South Highlands neighborhood that killed a 13-year-old Caddo Middle Magnet student when she was struck inside her grandparents’ home by a stray bullet. Prator knows that violent crime is a complex issue. It includes homicides, suicides, domestic violence, and mass shootings, like that one at a school in Uvalde, Texas, that killed 21 people. In many cases, there are mental health issues and other extenuating circumstances, and it can be hard, he said, to feel that you are making an impact. But law enforcement can have an impact on what Prator calls “street-corner violence,” like the South Highlands shooting.

“There’s two things there in ‘street-corner violence’ that I know we can impact,” Prator said. “One is offenders who are not being held accountable for illegal gun possession because of plea bargains and dismissed charges. The second part is the laws that allow us to hold them accountable.”

Prator believe a holistic community approach is necessary to combat violent crime. He has an 11-point plan that calls on law enforcement, state and local government, schools, church leaders, neighborhood associations, business leaders and the media to all play a role. “Everybody has a dog in the hunt,” Prator said. “And if you think you are doing all you can right now, that tells me you are satisfied. And if you are satisfied with the way things are going when 13-year-olds and 10-year-olds are getting shot and killed in running gun battles, then you are misled and in the wrong profession. It’s not just the police’s job to keep people safe. Historically it always been, ‘What are the police going to do about this violent crime?’ My mission in life has been to shine the light on others who have a dog in the hunt also.”

Prator knows the issue is not unique to Caddo Parish, but he knows this is where he can have the greatest impact right now. “I’m kind of a one-topic guy,” he said. “Until we do something about our violent crime, and holding people responsible who are committing violent crimes, and getting the proper laws to hold them responsible, I don’t see our area thriving. I realize it’s a national trend. But that doesn’t mean we have to be like the rest of the nation.”

Scott Anderson is a freelance writer with more than 20 years’ experience in journalism. He enjoys discovering and sharing people’s stories.

Scott Anderson is a freelance writer with more than 20 years’ experience in journalism. He enjoys discovering and sharing people’s stories.