The 318- area code doesn’t have many claims to fame, but one of the most enduring has been our place in true crime lore as the demise of the notorious outlaws Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker in Bienville Parish. The “Barrow Gang” (which included accomplices) went on their robberyand- killing spree during the Great Depression and the heyday of the “Public Enemy” era, from 1932 to 1934. However, Bonnie and Clyde first met in January 1930 in what was then considered the slum of West Dallas. Only a few weeks later, Clyde was arrested for auto theft and sent to the McLennan County Jail in Waco, Texas. A devastated Bonnie smuggled a gun to him in prison, which he used to break out in March of 1930. Seven days later, Clyde was recaptured and eventually sent to the Eastham Prison Farm, a notorious labor camp, where Clyde’s fortunes took drastic turns for the worse. A fellow inmate regularly sodomized Clyde, who eventually fought back and killed his attacker by crushing his skull with a pipe. Another inmate who was already serving a life sentence claimed responsibility for the murder.

In addition to this, with his slight build, Clyde feared he could not survive 14 years of hard labor and mutilated two of his toes with an axe to escape the work. In a cruel twist, due to his mother’s pleas for his release, only six days after he took this drastic measure, the state of Texas relented, and Clyde was released, scarred for life, bitter against the establishment, and a hardened criminal with a limp. It is believed his ensuing life of crime was meant to be revenge against the system for the ills he suffered in prison.

The Bonnie and Clyde legend eventually caught Hollywood’s imagination, with the most significant film ever made about the duo easily being “Bonnie and Clyde” from 1967, noted as one of the first films of the “New Hollywood” era and considered revolutionary at the time for its depictions of violence in film.

Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway played the starring roles (the fiasco at the 2017 Oscars where the pair presented the Oscar for Best Picture to the wrong movie, “La La Land,” was meant to be a commemoration of this movie), and it was also the film debut of Gene Wilder (of “Willy Wonka” fame). The film won two Oscars and, in 1992, was selected by the Library of Congress as being “Culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant,” which is the designation given to films selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. More recently, in 2019, Netflix released “The Highwaymen,” whichwas filmed in a significant part of Louisiana, using the authentic ambush site and the Old Louisiana Governor’s Mansion as the stand-in for the Texas Governor’s Mansion. This adaptation starred Kevin Costner and Woody Harrelson as the two retired Texas Rangers who came out of retirement to hunt down Bonnie and Clyde, Frank Hamer (the most decorated Texas Ranger of all time), and Maney Gault. Despite the acclaim of “Bonnie and Clyde,” and however shocking it may be to hear the words “Shreveport” and “Ringgold Road” in a movie (now Highway 154), neither film correctly depicts the fatal ambush (though “The Highwaymen” has original footage of the scene). Both show the pair as having stopped before they were fired upon, which historical accounts dispute, including firsthand accounts of the officers there: the lawmen opened fire while the car was slowing down to assist their fellow gang member Henry Methvin’s father, who, in cooperation with law enforcement, had a tire removed from his car to make it look like he needed help.

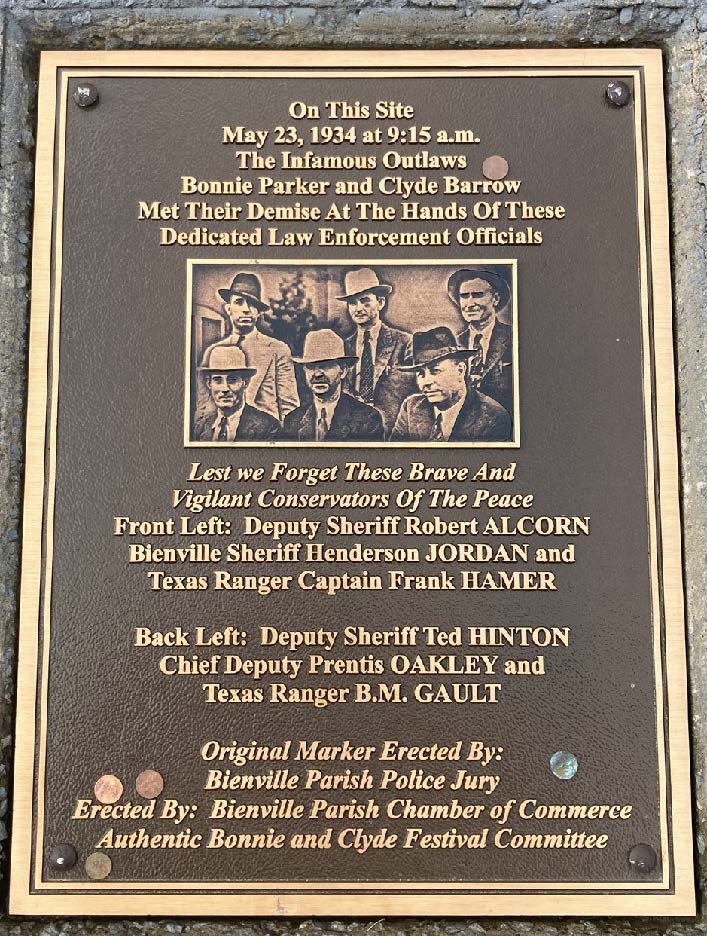

The group took no chances: a Louisiana officer and the youngest of the six, Prentiss Morel Oakley, fired the first shot (that he later admitted was premature), which struck Clyde in the head, killing him instantly. Bonnie’s ensuing scream was heard momentarily before the gunfire from the rest drowned it out. She was found with a half-eaten sandwich still in her hand that she had been eating when fired upon (the café she got that sandwich from, Ma Canfield’s Café, is now the Bonnie and Clyde Ambush Museum, still open to the public). In all, it is estimated that 167 bullets were fired, with 112 bullet holes counted on the car, with the coroner identifying 17 entrance wounds on Clyde and 26 on Bonnie. The embalmer reportedly had a difficult time embalming the two because of the massive number of holes in their corpses. Their brutal demise was considered well deserved: Bonnie and Clyde were known to have killed at least 13 people, nine of whom were law enforcement officers, between February 1932 and May 1934. While small-time robberies of convenience stores and gas stations were their preference, they also robbed banks (this being the Great Depression era; however, their bounty never exceeded $1,500) and frequently stole vehicles. Kidnapping was a regular occurrence, one instance of which occurred in Ruston when they kidnapped H. Dillard Darby (ironically, the mortician that would later work on Bonnie and Clyde, which Bonnie wryly predicted) and Sophie Stone while stealing Darby’s car. The gang took a liking to the two and released them in Arkansas instead of killing them. They followed a pattern of staying in midwestern states and the south, returning frequently to visit family members in Dallas. Staying constantly on the run between states took advantage of local law enforcement agencies not being allowed to cross state lines to pursue. Their most infamous hideout was the “Joplin hideout” on Oakridge Drive in Joplin, Missouri, where the gang holed up for 13 days before a shootout with police in April of 1933 that killed two police officers (this location is now an Airbnb that can be rented for just under $200 a night and was registered on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in May of 2009). From this hideout, poems and pictures were discovered, released to the press, and added to the gang’s notoriety.

While the ambush site is just south of Gibsland, Shreveport was a sort of staging area for the climactic shootout. Just two days before they were killed, the trio (Bonnie, Clyde, and Henry Methvin) had lunch at the Majestic Café, now 422 Milam Street. Methvin was sent to get the food while Bonnie and Clyde waited outside. Then, a Shreveport police car pulled up beside them, which spooked Clyde, and he took off without Methvin (this all revisited by “The Shreveport Times” last October). The next couple of days is when Hamer and his posse met up with Henry’s father, Ivy, who collaborated with them to set up the ambush with the promise of leniency for his son. At about 9:15 a.m. on May 23, the doomed couple drove into the trap in their tan Ford V8. There is a tombstone to mark the spot on the side of the road to this day. This “death car” they were shot in is currently on display at the Primm Valley Resort & Casino in Primm, Nevada, along with the blood-stained shirt Clyde wore when he was killed. To commemorate the occasion, Gibsland still holds a “Bonnie and Clyde Festival” every May, including reenactments of the ambush. While not everyone’s idea of something to celebrate, Bonnie and Clyde themselves knew they had it coming (“It’s death for Bonnie and Clyde,” Bonnie wrote in a poem), and an area could be known for worse things than ending outlaws’ reigns of terror.